|

© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 5b, s.

*Andrzej Habior

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity

Niealkoholowa stłuszczeniowa choroba wątroby a otyłość

Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Medical Centre for Postgraduate Education, Warsaw

Head of Department: prof. Jarosław Reguła, MD, PhD Streszczenie

Niealkoholowa stłuszczeniowa choroba wątroby (NAFLD) polega na nadmiernym nagromadzeniu ciał tłuszczowych (głównie triglicerydów) w hepatocytach. Ten stan nazywany stłuszczeniem wątroby jest łatwo rozpoznawany w badaniach obrazowych (USG) lub w badaniu histopatologicznym. Termin „NAFLD” jest zarezerwowany dla choroby polegającej na stłuszczeniu wątroby w związku z istniejącym u pacjenta zespołem metabolicznym i otyłością. W kontekście tej definicji, aby rozpoznać NAFLD, konieczne jest wykluczenie innych przyczyn stłuszczenia wątroby, do których między innymi należą leki, zakażenie wirusem hepatitis C, toksyny, niektóre choroby metaboliczne i co najważniejsze – nadmierne spożywanie alkoholu. Do niedawna powszechnie przyjmowano, że NAFLD jest spektrum różnie nasilonych zmian w wątrobie, od najłagodniejszej formy, jaką jest proste stłuszczenie, nazywane niealkoholowym stłuszczeniem wątroby (NAFL) do bardziej zaawansowanej formy – niealkoholowego stłuszczeniowego zapalenia wątroby (NASH). Według tej hipotezy nazywanej „teorią dwu uderzeń” (ang. „two hits”) choroba w wyniku pierwszego „uderzenia” („first hit”), jakim jest insulinooporność i zespół metaboliczny manifestuje się jako NAFL. Po drugim „uderzeniu” („second hit”) wywołanym na przykład endotoksynami napływającymi żyłą wrotną z jelit do wątroby, zmiany w wątrobie nasilają się, przybierają formę NASH i często postępują dalej, do zwłóknienia, marskości, a nawet raka wątrobowokomórkowego. Ostatnio pojawiło się inne wytłumaczenie patogenezy NAFLD. Według tej teorii NAFL i NASH są różnymi chorobami. W NAFL triglicerydy nagromadzone w hepatocytach pełnią rolę ochronną i choroba nie postępuje do NASH. Natomiast u innych osób, w wyniku równoczesnego działania wielu czynników (teoria „multi hit”) powstają zmiany zapalne a następnie włóknienie. Czynnikami usposabiającymi do NASH są między innymi mikroflora jelitowa, cytokiny produkowane w wisceralnej tkance tłuszczowej, stres metaboliczny w strukturach siateczki gładkiej endoplazmatycznej hepatocytów i dysbioza indukowana przez inflammasomy. NAFLD i NASH są jednymi z najczęstszych chorób wątroby w skali światowej. W wysoko rozwiniętych krajach europejskich NAFLD występuje do 44% populacji i koreluje z „epidemią” cukrzycy i otyłości. Ostatnie badania wykazały, że mikroflora jelitowa, która jest jednym z głównych czynników powstawania NASH odgrywa również rolę w powstawaniu otyłości, która z kolei także usposabia do NAFLD i NASH. W ostatniej części przeglądu omówiono rolę rosnącego spożycia fruktozy (szczególnie pod postacią stężonego syropu) w powstawaniu otyłości, insulinooporności, a także rolę tego powszechnie stosowanego w przemyśle spożywczym środka słodzącego w inicjowaniu zmian zapalnych w wątrobie prowadzących do NASH. Słowa kluczowe: wątroba, stłuszczenie, stłuszczeniowa choroba wątroby, otyłość

Summary

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as the accumulation of fat (mainly triglycerides) in the liver cells. This condition termed as hepatic steatosis is easily visualised on ultrasound or on liver histology. The term NAFLD is reserved for the liver disease that is predominantly associated with metabolic syndrome and obesity. In the context of this definition the exclusion of secondary causes of liver steatosis (medications, virus hepatitis C, toxins, some metabolic diseases and other medical conditions and, what is most important, excessive alcohol consumption) is mandatory for NAFLD diagnosis. NAFLD is categorised into simple steatosis, termed nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). According to the first “two hit” model of pathogenesis, NAFLD presents the wide spectrum of liver changes. Insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome, acting as a “firs hit” result in NAFL. After a “second hit” (e.g. gut-derived endotoxins), NAFL progress to NASH, the more advanced form of NAFLD. Furthermore, NASH frequently progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis and even to hepatocellular carcinoma. Recently, a new model of pathogenesis of NAFLD has been proposed. According to this model, NAFL and NASH are the distinct conditions. In NAFL the intrahepatic triglycerides exert rather protective effect and the disease does not progress to NASH. In other patients, many factors (“multi hit” theory) acting in parallel, result in liver inflammation (NASH). Gut microbiota and adipose tissue derived cytokines, endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammasome mediated dysbiosis and other, actually less known factors, may play a central role in NASH developing. NAFLD and NASH are common causes of chronic liver diseases worldwide. In Western countries NAFLD is the most common liver disease (up to 44% in the general European population) closely associated with the epidemic of diabetes and obesity and is increasingly relevant public health issue. Recently published studies shown, that gut microbiota, which may be in important risk factor of NASH, may also predispose the host to obesity. In the last part of this review the role of growing consumption of fructose (especially in form of high fructose corn syrup) in development of obesity and insulin resistance and also in triggering of hepatic inflammation (NASH) is discussed. Key words: liver, steatosis, fatty liver disease, obesity

INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

This article is published in a volume of „Postępy Nauk Medycznych” fully dedicated to simple obesity. The author recognized as purposeful to present the subject of NAFLD/NASH in broader perspective, because it is related to the problem of obesity.

Fatty liver, which refers to the build-up of lipids, mainly triglycerides (TG), in hepatocytes, is a pathological condition, well known for a long time, and it refers to an imbalance between the amounts of lipids inflowing to the liver or produced in the liver, and the amount being secreted in the form of very low density lipoproteins (VLDL). An excessive amount of TGs in the liver parenchymal cells is the most common type of nonspecific response of the organ to various harmful factors and usually it is reversible after the causal factor stops acting. One of the most common causes of fatty liver is ethyl alcohol, and this pathology is a classical example of the reversibility of hepatic lesions following the discontinuing intake of a substance causing fatty liver. There are many known factors and conditions which may lead to fatty liver (1). They include improper nutrition and lifestyle, congenital or acquired diseases, as well as numerous exogenous factors, such as drugs and other chemicals (tab. 1 and 2).

Table 1. Exogenous factors, diseases and other pathological conditions, which may be accompanied by fatty liver (1).

Table 2. Some well known and generally used drugs, which may lead to fatty liver (6).

In 1980, Ludwig et al. pointed out for the first time that after ruling out alcohol during interviews with subjects as a cause of their fatty liver, there are some cases with a morphological picture, which is “richer” than simple fatty liver. These cases revealed signs of hepatitis and fibrosis of various intensities (2). There were the first descriptions of a new disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatits (NASH), which has been interesting for clinicians and representatives of basic sciences involved in hepatology for three decades. During the initial period of studies, a definition was established for the liver pathology including steatosis, as well as expressions (see further in document), which are binding till now with some modifications. Aforementioned pathologies include: nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which comprises two types of pathologies – nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatits (NASH).

In 1998, Day and James presented a concept of NASH pathogenesis (3). According to this hypothesis, NASH is being developed in two “hits”. The first “hit” is simple steatosis, which is facilitated by insulin resistance, and the second “hit” includes developing inflammation, apoptosis and necrosis in hepatocytes, which results from oxidative stress induced by many factors – mainly by proinflammatory cytokines, environmental and genetic factors. This pathogenesis of NASH was generally accepted till the end of the first decade of this century, when new concepts occurred (see further).

The increasing interest in liver diseases belonging to NAFLD group and a need to improve the quality of diagnoses and accuracy in communication, not only among scientists, but also in everyday clinical practice, forced the conduction of works on classification of morphological lesions in the liver. The first histopathological classification of NASH, which has been used till now, was developed in 1999 by Brunt et al. (4). Since 2005, more precise, but more time-consuming score classification has been available, which considers a significantly larger number of parameters than the classification by Brunt et al. However, due to its complexity, score classification of NASH is almost exclusively used in scientific publications (5).

In the 1980’s, before distinguishing NAFLD as a new disease, steatosis was treated as a histopathologic abnormality included in the picture of a specific disease or syndrome. Then, the term “NAFLD” referred to various pathological conditions with steatosis in the course of a disease, while most frequently it meant the toxic action of drugs and no association with any specific disease (e.g. Wilson’s disease), provided that alcohol etiology was ruled out. Not until 2002, the criteria of diagnosing NAFLD were narrowed and it was adopted that this expression referred only to fatty lesions in the liver observed in persons with insulin resistance and clinical, extrahepatic symptom of this abnormality, which is metabolic syndrome, or its individually occurring components – overweight or obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia (shadowed area in tab. 1). All other causes of fatty liver listed in tables 1 and 2 are currently recognized as falling out of the diagnosis of NAFLD and they are referred to as secondary fatty liver (6).

Despite a significant number of scientific studies and clinical observations, problems of fatty liver disease are not well known and many questions and doubts regarding pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment, and especially regarding prognosis in NAFLD remain unanswered. The latter mainly refers to NASH because of the increasing evidence for the progressive nature of this disease, which in a substantial percentage of cases leads to advanced fibrosis (37-41%), cirrhosis (over 5%) and even to liver cancer, and in general evaluation, it leads to a significantly higher mortality rate than it is in the general population (7-9). In order to summarize current knowledge about NAFLD, to determine direction for the studies and to provide clinicians with management based on the highest quality evidence, prestigious liver associations – European (European Association for the Study of Liver, EASL) in 2010 (10) and American (American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, AASLD) together with two American gastroenterological associations: American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) in 2012 (11) published a formal position (10) and guidelines (11) for management of NAFLD.

The purpose of this publication is to familiarize Polish readers of „Postępy Nauk Medycznych” with the most important, and above all, practical information regarding NASH based on the aforementioned guidelines and more recent publications as well as to discuss some aspects connecting NAFLD/NASH with the “obesity epidemic”, which has been recently observed all over the world.

DEFINITIONS, EPIDEMIOLOGY, DIAGNOSIS OF NAFLD, NAFL AND NASH

It is assumed that the expression “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease” (NAFLD) refers to the liver pathology related to systemic metabolic abnormalities, including insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome developing on its basis. NAFLD does not include alcoholic damage (steatosis) and previously listed (tab. 1 and 2) secondary fatty liver (fig. 1). NAFLD includes two forms – less advanced, i.e. nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In the microscopic picture, NAFL reveals simple steatosis (with no signs of hepatocyte damage), but NASH, in addition to hepatocyte steatosis, reveals the following signs, which are observed in various intensities and in various combinations (4, 5): lobular hepatitis, hepatocyte necrosis, Mallory’s hyaline, glycogen degeneration of liver cell nuclei, fibrosis/cirrhosis.

Fig. 1. Classification of fatty liver diseases.

Global epidemiological data regarding the incidence of NAFLD and two forms of this syndrome – NAFL and NASH, are highly diverse, depending on the region, the studied population as well as the criteria and investigation methods. The incidence of NAFLD diagnosed based on an ultrasound evaluation ranges from 17% to 46% depending on the world region. Percentages in Europe are higher than they are in Asia (20-30% vs. 15%, respectively). These percentages stand in contrast with the results obtained in living liver donors – histologically documented NAFLD was established in 12-18% of potential donors in European centres, 27-38% – in the U.S. and in as much as 51% of healthy subjects donating part of the liver in Korea (10, 11). The most recent review of European epidemiological data demonstrates that the incidence of NAFLD in the population of our continent (including children and obesity) ranges from 2% to 44%, and among subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus, it amounts to 42.6-69.5% (12). The incidence of NASH is estimated at the level of 3-5% in the general population of developed countries. Recent American studies show that among subjects with NAFLD diagnosed based on ultrasound evaluation, histologically confirmed NASH was diagnosed in 12.2% (13). Large epidemiological studies regarding fatty liver disease have not been conducted in Poland. Results of autopsies recently conducted in children, who died in accidents, may contribute to clarifying the incidence of this pathology. In nearly 350 subjects, 5.3% were diagnosed with fatty liver and 0.3% with NASH. It has to be emphasized that 54.4% of children with fatty liver were overweight (14).

In order to diagnose NAFLD, it is necessary to meet 2 conditions (10, 11):

1. Confirming fatty liver (with imaging tests or histopathological evaluation).

2. Ruling out alcohol as a potential etiological factor of the disease and ruling out other causes of steatosis (so-called secondary fatty liver).

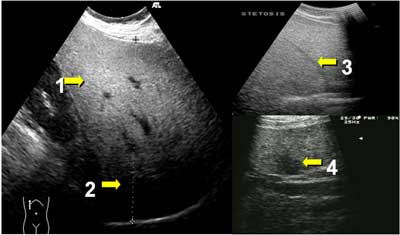

Fatty liver may be diagnosed if fat bodies comprise more than 5% of the liver cell mass. Before the common access of imaging evaluation methods, such as ultrasound evaluation (USG) or computed tomography scan (CT-scan), fatty liver was diagnosed at an autopsy table or as a result of a histopathological evaluation of a section collected during a surgical procedure. In this second case, it is easy to confirm steatosis in a basic histopathological evaluation, which is hematoxylin and eosin staining. Currently, liver tissue is collected for diagnostic purposes during a percutaneous liver biopsy procedure. However, a core needle biopsy is an invasive procedure and for this reason, histopathological evaluation is not obligatory in each case when fatty liver disease is suspected, therefore non-invasive imaging diagnostics is performed first. The diagnostic value of modern imaging methods – USG, CT-scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in diagnosing fatty liver is high (sensitivity and specificity > 90%) and comparable. Due to costs, availability and easy performance, ultrasound is the most frequently used method in diagnostics of NAFLD. However, it should be kept in mind that the result of an ultrasound evaluation largely depends on the quality of the devices and subjective interpretation of the physician performing the test. Finding four abnormalities is necessary in order to establish a reliable diagnosis of fatty liver in ultrasound evaluation (fig. 2). In practice, it is not uncommon that as a result of rush or poor image quality, a physician who performs the ultrasound test establishes a diagnosis of fatty liver based on only one parameter, i.e., parenchymal hyperechogenicity (the “white liver”), which leads to the situation that fatty liver is overdiagnosed.

Fig. 2. Diagnosis of fatty liver based on ultrasound evaluation.

1 – parenchymal hyperechogenicity, 2 – intensified attenuation, 3 – poorly visible vessels, 4 – focal hyposteatosis. Presence of all four signs leads to diagnosis of fatty liver (courtesy of Dr. I. Gierbliński). Meeting the second necessary condition for diagnosing NAFLD is more difficult, because it requires very careful interview and conducting an extensive laboratory evaluation. First, alcoholic liver disease should be ruled out, because in most cases it manifests with steatosis. Based on numerous epidemiological studies, the European guidelines assume that consuming less than 20 g of alcohol per day by females and < 30 g/day by males theoretically rules out alcoholic fatty liver disease (10). Then, liver diseases should be ruled out in such cases, where morphological lesions, which are characteristic for a given pathology, are accompanied by fatty liver (tab. 1). Above all, autoimmune and viral hepatitis (in particular, HCV genotype 3) and genetic diseases (i.a., Wilson’s disease) should be considered.

NAFLD coexists with metabolic disturbances, which meet criteria for metabolic syndrome or one or a few components of this syndrome (obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and hypertension). If phenotypic signs of metabolic syndrome are established in a patient, then diagnosing NAFLD based on an interview and imaging evaluation is highly likely, so in order to rule out other causes of steatosis, further evaluation may be limited. However, it should be kept in mind that no interview, no basic laboratory evaluation and no imaging tests, which support diagnosis of NAFLD, are able to differentiate between NAFL and NASH. The “gold standard” for a NASH diagnosis is a histopathological evaluation of a biopsy liver sample (4, 5, 10, 11). However, considering that it is an invasive procedure, a common sense approach should be exercised, while making a decision on biopsy.

In recent years, there has been an intensive search for non-invasive methods to evaluate the presence and intensity of inflammatory lesions as well as the presence and progress of fibrosis, and thus to diversify whether a patient with NAFLD reveals simple steatosis (NAFL) or NASH. The suitability of the two groups of methods is under evaluation: a) various laboratory panels – so-called diagnostic algorithms and b) imaging tests. Due to numerous analyses and opinions, it is difficult to explicitly establish which method is the best and which of them is able to replace the histopathological evaluation of the liver. The only thing certain is that none of the proposed non-invasive methods provides comprehensive evaluation of all morphological lesions in the liver. A suitability analysis of non-invasive methods for NAFLD diagnostics, which has been published this year, demonstrates which test out of those currently available in practice is the best for evaluation of specific conditions or parameters (15). Hence, USG is still the first-line test for the detection of steatosis. The sensitivity of USG in diagnosing simple steatosis may be increased with a biochemical test panel (the “Steato Test”). Serum concentration of cytokeratin 18 is currently the best marker of an “inflammatory condition” in NASH. However, the analysis has not explicitly indicated, which non-invasive test is the best in evaluating progress of fibrosis. Three tests based on laboratory panels (“FibroMeter”, “FIB-4” and “NAFLD fibrosis score”) and ultrasound elastography (15) are of comparable value. Recently, significant interest has been generated by a method based on ultrasound elastography technique (Controlled Attenuation Parameter, CAP) recommended as s good tool for evaluation of fatty liver (16).

PATHOGENESIS OF NASH

As it was mentioned in the introduction, over more than three decades after selecting new diseases out of the group of fatty livers – NAFLD/NASH – only one pathogenetic model was binding, the one that was proposed by Day and James (3). Fatty liver was meant to include gradual occurrence of lesions in the liver starting from simple steatosis, through inflammation (NASH), fibrosis and ending with cirrhosis. Onset of the disease and consecutive stages were initiated by two “hits”. The first “hit” caused fatty liver, and the second “hit” – inflammation and its further consequences. At the end of the first decade of this century, a hypothesis was presented, which stated that NASH is created in a healthy liver as a result of action of many factors predisposing to steatosis and inflammation (“multi hit”). However, in predisposed patients, it would lead only to fatty liver (e.g. with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome) and NAFL occurs without progression to NASH and cirrhosis (17). According to this hypothesis, NAFL and NASH do not fall into the spectrum of NAFLD, but they are two, independent diseases (fig. 3) (18).

Fig. 3. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) – two different diseases?

A list of factors “hitting” the liver, which leads to the inflammatory process with steatosis and fibrosis, is long and diverse (tab. 3). The role of some of these factors is well-documented, and the role of others – is still under analysis.

Table 3. Factors initiating fatty liver, hepatitis and hepatic fibrosis, i.e., nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) (17-19).

Intestinal microflora

Quantitative and qualitative changes in intestinal flora and corresponding bacterial endotoxins coming to the liver through the portal circulation stimulate TNF?. This is a factor out of the “multi hit” group causing NASH, which was suggested a long time ago (17), but which has been recently confirmed (20).

Inflammasomes

There are recently discovered complexes of intracellular proteins, which activate caspase-1 and lead to the release of proinflammatory cytokines in response to signals of cellular damage. It leads to inflammation, apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes (17, 21, 22).

Due to modern techniques in molecular biology (Genome Wide Association Study, GWAS) many genes were discovered – they are candidates to be considered as the ones playing the role in the pathogenesis of NASH (17, 19, 23). However, this is the beginning of studies and therefore knowledge on this subject is uncertain and it does not correspond to clinical practice.

OBESITY AND NAFLD

Relationship between obesity and fatty liver disease has been known for a long time. It has been established that a majority of patients with NAFLD reveal metabolic syndrome, with pathogenetic basis of insulin resistance, and phenotypic factors such as: glucose intolerance or clinically manifested type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity (especially central obesity), dyslipidemia and hypertension. Among listed “components” of metabolic syndrome, obesity is a global problem due to epidemiological reasons. According to data provided by WHO (www.who.org), over 1.6 billion adults all over the world suffer from overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2), and at least 0.5 billion – from obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2). Statistic data of the European Union provide that over 15% of males and over 22% of females in Europe suffer from obesity, and what is the most important, these rates are getting worse year by year (fig. 4). The incidence of NAFLD increases together with BMI (tab. 4). As it is presented in the table 4, the majority of subjects with pathological obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) reveal fatty liver disease.

Fig. 4. Prevalence of obesity in adult populations of some European countries.

Table 4. Prevalence of two forms of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) – NAFL and NASH depending on BMI (24).

Obesity is a global problem, and NAFLD is the most common liver disease in developed countries, and therefore, high epidemiological rates may partially justify coexistence of these diseases. However, the main reason for the high coincidence of both diseases is their relationship with metabolic syndrome. Moreover, numerous studies conducted in recent years demonstrated that some factors initiating the inflammatory process in the liver, which leads to creating the picture of NASH (previously discussed new hypothesis of “multi-hit”), also play the role in pathogenesis of abdominal (visceral) obesity. Such action is revealed by adipokines and other cytokines, especially coming from visceral adipose tissue, as well as the intestinal microflora and probably inflammasomes (17, 19- 22).

Studies conducted in recent years revealed a new “common point” between obesity and NAFLD, which refers to fructose coming from corn, and in practice – a food product form of this sugar – fructose syrup. Regular corn syrup contains glucose. However, syrup treated with enzymes in order to intensify sweet taste mainly contains fructose. The commercial name of fructose syrup made of corn is HFC55, which means that fructose constitutes 55% of its content. It has been established, beyond reasonable doubt, that consuming large amounts of fructose reveals significantly adverse action. It disturbs the metabolism of glucose, glycogen, lactates and free fatty acids, which leads to insulin resistance, obesity, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia (17, 25-27). Consumption of fructose syrup is enormous. It is commonly used for sweetening all beverages and meals (the perversity of some commercials has to be emphasized because they inform that a given product does not contain any sugar) and it cannot be ruled out that it has become one of the main reasons for epidemic obesity recently observed all over the world.

Previously, the uncertain role of fructose syrup in the pathogenesis of NASH has been recently proven (28), and in addition, it has been demonstrated that excess fructose in a diet accelerates the progression of NASH to cirrhosis (29). On this basis, therapeutic recommendations for patients with fatty liver disease include an increase in physical activity and use of a suitable diet (these recommendations are related to the goal of losing weight and obtaining positive metabolic results) were extended with a recommendation to avoid beverages and meals containing fructose syrup made of corn (11). Piśmiennictwo

1. Puri P, Sanyal A: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: definitions, risk factors, and workup. Clinical Liv Dis 2012; 1: 99-103.

2. Ludwig J, Viggiano T, McGill D, Oh B: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo Clinc with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1980; 55: 434-438.

3. Day C, James O: Steatohepatitis: a tale of two ”hits”. Gastroenterology 1998; 114: 842-845.

4. Brunt E, Janney C, Di Bisceglie A et al.: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol 1999; 94: 2467-2474.

5. Kleiner D, Brunt M, Van Natta M et al.: Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 41: 1313-1321.

6. Angulo P: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 1221-1231.

7. Mehta R, Younossi Z: Natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clinical Liv Dis 2012; 1: 112-113.

8. Adams L, Lymp J, Sauver J et al.: The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based kohort study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 113-121.

9. Ong J, Pitts A, Younossi Z: Incerased overall mortality and liver-related mortality in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2008; 49: 608-612.

10. Ratziu V, Bellentani S, Cortez-Pinto H et al.: A position statement on NAFLD/NASH based on the EASL 2009 special conference. J Hepatol 2010; 53: 372-384.

11. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine J et al.: The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology 2012; 55: 2005-2023.

12. Blachier M, Lelu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M et al.: The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol 2013; 58: 593-608.

13. Williams C, Stenger J, Asike M et al.: Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 2011; 140: 124-131.

14. Rorat M, Jurek T, Kuchar E et al.: Liver steatosis in Polish children assessed by medicolegal autopsies. World J Pediatr 2013; 9: 68-72.

15. Festi D, Schiumerini R, Marzi L et al.: The diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Availability and accuracy of non-invasive methods. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37: 392-400.

16. Myers R, Pollett A, Kirsch R et al.: Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP): a noninvasive metod for the detection of hepatic steatosis based on transient elastography. Liver Int 2012; 32: 902-910.

17. Tilg H, Moschen A: Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology 2010; 52:1836-1846.

18. Yilmaz Y: Review article: is non-alcoholic fatty liver disease a spectrum, or are steatosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis distinct conditions? Alimentary Pharmacol Ther 2012; 36: 815-823.

19. Farrell G, van Rooyen D, Gan L, Chitturi S: NASH is an inflammatory disorder: pathogenic, prognostic and therapeutic implications. Gut Liver 2012; 6: 149-171.

20. Mouzaki M, Comelli E, Arendt B et al.: Intestinal microbiota in patients with non- alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013 Feb 11. doi: 10.1002/hep.26319. [Epub ahead of print]

21. Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Jin Ch et al.: Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature 2012; 482: 179-185.

22. Csak T, Ganz M, Pespisa J et al.: Fatty acid and endotoxin activate inflammasomes in mouse hepatocytes that release danger signals to stimulate immune cells. Hepatology 2011; 54: 133-144.

23. Dongiovanni P, Anstee Q, Valenti L: Genetic predisposition in NAFLD and NASH: impact on severity of liver disease and response to treatment. Curr Pharm Des 2013 Feb 4. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S: Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology 2010; 51: 679-689.

25. Bray G, Nielsen S, Popkin B: Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 537-543.

26. Ferder L, Ferder M, Inserra F: The role of high-fructose corn syrup in metabolic syndrome and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 2010; 12: 105-112.

27. Moeller S, Fryhofer S, Osbahr A et al.: The effects of high fructose syrup. J Am Coll Nutr 2009; 28: 619-626.

28. Lim J, Mietus-Snyder M, Valente A et al.: The role of fructose in the pathogenesis of NAFLD and the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 7: 251-264.

29. Vos M, Lavine J: Dietary fructose in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013; doi: 10.1002/hep.26299.

otrzymano/received: 2013-02-19 zaakceptowano/accepted: 2013-02-27 Adres/address: *Andrzej Habior Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Medical Centre for Postgraduate Education ul. W. K. Roentgena 5, 02-781 Warszawa tel.: +48 (22) 546-23-28, fax: +48 (22) 546-30-35 e-mail: ahab@coi.waw.pl Artykuł Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obesity w Czytelni Medycznej Borgis. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chcesz być na bieżąco? Polub nas na Facebooku: strona Wydawnictwa na Facebooku |