|

© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 8, s. 543-547

*Aneta Obcowska1, Małgorzata Kołodziejczak2, Iwona Sudoł-Szopińska2, 3, 4

Przydatność przedoperacyjnego badania endosonograficznego w różnicowaniu przetok odbytu niskich z wysokimi

The usefulness of preoperative endosonographic differentiation of low and high anal fistula

1Department of General Surgery, Vascular Surgery Unit, Praski Hospital, Warsaw

Head of Department: Rafał Górewicz, MD, PhD 2Department of General Surgery, Proctology Unit, Solec Hospital, Warsaw Head of Department: Jacek Bierca, MD, PhD Head of Unit: Małgorzata Kołodziejczak, MD, PhD 3Department of Radiology, Institute of Rheumatology, Warsaw Head of Department: prof. Iwona Sudoł-Szopińska, MD, PhD 4Department of Diagnostic Imaging, II Medicine Faculty, Medical University, Warsaw Head of Department: prof. Wiesław Jakubowski, MD, PhD Streszczenie

Wstęp. Przedoperacyjne określenie wysokości przetoki ma duże znaczenie w wyborze sposobu leczenia oraz ocenie ryzyka pooperacyjnej inkontynencji. Ze zwiększonym ryzykiem wystąpienia tego powikłania wiąże się leczenie wysokich przetok przezzwieraczowych i międzyzwieraczowych, przetok nadzwieraczowych, rozgałęzionych, w tym podkowiastych, oraz przetok przednich u kobiet. Cel. Celem pracy było określenie czułości i swoistości badania endosonograficznego (ang. endoanal ultrasound – EUS) w ocenie typu kanału pierwotnego oraz wysokości przetoki odbytu. Materiał i metody. Materiał stanowiła grupa 424 pacjentów, w tym 132 kobiet i 292 mężczyzn w średnim wieku 45,8 lat, zoperowanych z powodu przetoki odbytu w okresie od 1 grudnia 2008 do 8 kwietnia 2011 roku. Przeprowadzono retrospektywną analizę danych z 424 przedoperacyjnych badań EUS oraz protokołów operacyjnych u tych samych pacjentów. Sprawdzono zgodność oceny przetok pod względem typu kanału pierwotnego oraz jego wysokości. Wyniki. W EUS stwierdzono 63,1% przetok niskich i 36,9% wysokich, zaś śródoperacyjnie odpowiednio 57,6 i 42,2% przetok (w 0,2% przypadków stwierdzono przetokę mnogą). Zgodność EUS ze stanem śródoperacyjnym w ocenie wysokości przetoki uzyskano w 344 przypadkach (84,3%). Czułość i swoistość tej metody w ocenie wysokości przetok wyniosły odpowiednio 75 i 91%. Wnioski. Badanie EUS jest dobrym badaniem dodatkowym do określania wysokości przetoki, niezależnie od jej typu. Czułość i swoistość metody w ocenie wysokości przetok wynosi odpowiednio 75 i 91%. Słowa kluczowe: przetoka odbytu wysoka, badanie endosonograficzne, typ kanału pierwotnego

Summary

Introduction. Preoperative determination of the fistula is of great importance in the selection of treatment and the risk of postoperative incontinence. High transsphincteric and intersphincteric fistulas, suprasphincteric fistulas, branching ones, including horseshoe ones and front fistulas in women are associated with an increased risk of complications related to treatment. Aim. The aim of this study was to determine the sensitivity and specificity of endosonographic examinations (EUS – endoanal ultrasound) to determine the type of the original canal and the location of anal fistula. Material and methods. The material was a group of 424 patients, including 132 women and 292 men with a mean age of 45.8 years, operated because of anal fistula in the period from 1 December 2008 to 8 April 2011. A retrospective study of 424 preoperative EUS examinations and operational protocols in the same patients was conducted. The compatibility of the assessment of fistulas in terms of type of canal and its original location was verified. Results. In EUS examinations 63.1% low fistulas and 36.9% high fistulas were determined, and intraoperatively, respectively 57.6 and 42.2% of fistulas (in 0.2% of cases plural fistula was determined). EUS compliance with the state of the intraoperative assessment of the fistula was obtained in 344 cases (84.3%). The sensitivity and specificity of this method in the evaluation of fistulas were respectively 75 and 91%. Conclusions. EUS is a good additional examination for the determination of the fistula location, regardless of its type. The sensitivity and specificity of the method in the assessment of fistula is respectively 75 and 91%. Key words: high anal fistula, endoscopic ultrasound, the type of the original canal

Introduction

Anal fistula is described has been described in the medical literature for more than 2.5 thousand years.

To date, the disease has gone through a number of pathophysiological theories, classifications and a series of proposed treatments. The treatment of anal fistula is often problematic and leaves the surgeon with a choice between the courageous operational procedure with a lower risk of disease recurrence with simultaneous increased risk of postoperative incontinence (urinary and bowel gas) and cautious procedure, giving more relapses, but less complications of incontinence. The recurrence rate quoted in the literature depends on, among other things, the type of operation performed, and in the case of fistulotomy eq3uals 0-11% (1, 2), using the surgical technique of a displaced muscle flap 1.5-4.6% (3, 4), anodermal flap-plastry 0-3% (5-10), the Hippocratic operation method 4-39% (2, 11-13). Leaving the internal opening and insufficient expertise of a surgeon are also factors increasing the risk of reoccurrence (1).

The most serious postoperative complication is urinary incontinence due to sphincter damage. The first scale to evaluate the severity of fecal and gas incontinence was developed by Parks and Browning (14). The currently most commonly used classifications are the ones of Wexner or Vaizeya (15, 16). The risk of incontinence and anal fistula after the operation is 0 to 25% (urinary incontinence), and even up to 60% (periodic dirty linen) (1, 6, 17, 18). High fistulas, apart from the branching ones (including horseshoe ones), front fistulas in women, recurrent fistulas, also formed after irradiation, and in the course of Crohn’s disease are known as the so-called “complex” fistulas (19).

Their operation is associated with increased rates of postoperative incontinence. Some authors believe that another risk factor for incontinence are more previous incision and drainage of anus abscess (20). In centers specializing in colorectal surgery postoperative complication rate is much lower than in the general chirurgic branches.

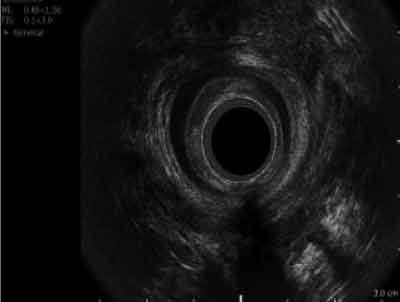

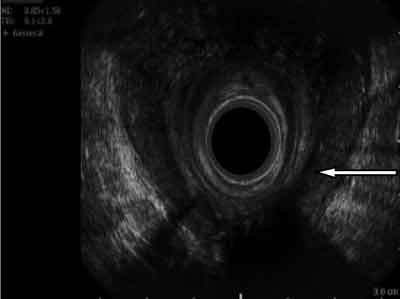

The determination of a fistula location is essential for the proper planning of the operation and evaluating the risk of complications. The canal is described as high when it covers more than 30% of the length of the anal external sphincter muscle (21) (fig. 1, 2).

Fig. 1. Back high transsphincteric fistula.

Fig. 2. Back high horseshoe intrasphincteric fistula.

Aim

The aim of this study was to determine the sensitivity and specificity of endosonography examinations (EUS – endoanal ultrasound) to determine the type and height of the original canal of anal fistula.

Material and methods

The material was a group of 424 patients, including 132 women and 292 men, aged between 17 and 83 years (mean 45.8 years), operated because of anal fistula in the period from 1 December 2008 to 8 April 2011. The analysis does not include vaginal-rectal fistulas, fistula arising in the course of Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, cancer, against the presence of a foreign structure, and after irradiation of the anal area. The study included only patients scheduled for elective surgery, except of emergency cases operated because of concomitant anal abscess.

A retrospective comparative analysis of data from 424 EUS examinations and operational protocols in the same patients was conducted.

All EUS examinations were performed by a single, experienced radiologist with Profocus Ultraview 2202-7 apparatus with endorectal 3D mechanical head, with a frequency of 16 MHz. The examination was performed in the Sims position, without bowel preparation. Transrectal probe was coated with ultrasound gel, and a latex sheath, which was also applied to the gel. The type of fistula was determined, the height, the location of the internal opening, the presence of any branches, morphological condition of sphincters. A similar analysis was conducted during the operation. Parks classification was used in the assessment (22). Fistulas were included in the group of high ones when covered more than 1/3 the length of the external anal sphincter muscle.

Concordance between the preoperative assessment of anal fistula in study EUS for the entire group was determined, as well as for different types of original canals. The sensitivity and specificity of EUS in these groups were calculated. For the calculations, the χ2 of Pearson independence test was used.

Results

In the EUS examination the following were diagnosed: 100 intersphincteric fistulas (23.6%), 266 transsphincteric fistulas (62.8%), 45 suprasphincteric fistulas (10.6%), 9 extrasphincteric fistulas (2.1%) and 4 unusual (submucosal) ones (0.9%). Intraoperatively following were diagnosed, respectively, 67 (15.8%) intersphincteric fistulas, 265 (62.5%) transsphincteric fistulas, 74 (17.5%) suprasphincteric fistulas, 17 (4.0%) extrasphincteric fistulas, 1 (0.2%) unusual fistula (submucosal).

For the entire group conformity assessment primary channel type was found in 312 cases (73.6%).

In the EUS 263 fistulas were determined as low (63.1%) and 154 as high ones (36.9%) (tab. 1). Intraoperatively 236 were determined as low fistulas (57.6%) and 173 as high ones (42.2%). In 1 patient plural fistula was diagnosed (0.2%) (tab. 2). Statistical analysis concerned 407 cases. The analysis excluded 17 cases because of the lack of data in EUS and operational protocols. Compliance of EUS with the intraoperative assessment of fistula was achieved in 344 patients (84.3%). 130 cases were properly classified in the group of high fistulas and 214 cases in the group of low fistula (tab. 3). The accuracy of method classification (ACC) is equal to 84.5%. The sensitivity and specificity of this element in the assessment of fistula were respectively 75 and 91%.

Table 1. Number of low and high fistulas according to EUS.

*cases excluded from the analysis due to lack of complete ultrasound data

Table 2. Number of low and high fistulas according to intraoperative examination.

**cases excluded from the analysis due to lack of complete operational protocols’ data

Table 3. Contingency of the first and second type error estimation for a variable height of fistula in EUS examination.

The results of separately analyzed fistula groups of low and high intersphincteric and low and high transsphincteric fistulas are shown in table 4. Suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric fistulas are inherently high, because in these groups accuracy of the original canal type assessment was synonymous with the accuracy of the fistula assessment.

Table 4. Sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of EUS in determining the height of fistula depending on the type of the original canal.

Discussion

High anal fistula operations require experience as they are related to the risk of extensive damage to the anal sphincter. In particular, this applies to patients operated due to recurrent fistula or sphincter failure symptoms occurring preoperatively. Diagnostic stage is important in order to minimize the risk of postoperative incontinence. It is essential that a proper definition of the fistula is performed, as it is one of the decisive factors for the choice of surgical procedure and it informs on the increased risk of postoperative incontinence. Classic treatment of high fistula involves the intersection of a large part of the external sphincter. Thus, many times, especially in the presence of other risk factors for incontinence, it will prompt the surgeon to choose the Hippocratic operation or implement additional sphincter plastry or use more conservative methods, saving sphincter to a greater degree, such as displaced anoderm flap plasty or the use of tissue adhesives and caps. Preoperative determination of the original canal is also important, however, to a lesser extent than a differentiating the low and high fistula. A low intersphincteric fistula and low transsphincteric fistula are usually operated by fistulotomy, in the case of high transsphincteric fistulas suprasphincteric fistulas partial sphincterotomy and thread drainage are used (Hippocratic surgery) or displaced anoderm flap plasty. Similar surgical techniques are used in high intersphincteric fistula, in exceptional cases, in patients with a very good continence, fistulotomy can be used.

The leading diagnostic imaging in the diagnosis of anal fistula are EUS examinations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In everyday practice EUS is often performed because of greater availability, uncomplicated procedures and low cost of the examination. However, our preliminary experiments (data not shown) indicate that, in the case of recurrent fistulas, particularly complex ones, MRI is a more accurate method, especially in the evaluation of branching and the type of fistula.

Publications about the value of EUS in the diagnosis of anal fistula concern its compliance in the assessment of: primary canal type, the location of the internal opening and branches. So far, none of the publications in the available literature analyzed the accuracy of EUS for differentiating anal fistulas, which was the subject of our paper. The published data of EUS in the evaluation of the conformity of the original canal type assessment ranges from 61 to 100% (23-35), the assessment of the internal opening 11-86% (23-27, 33), the assessment of horseshoe branching 50-91% (23-27, 33). Narrow or filled with inflammatory granulation tissue canals are often misinterpreted as postoperative scars. Improving the efficiency of the method (the assessment of the original canal, branching and the internal opening) can be obtained by the administration hydrogen peroxide solution into the fistula canal (26, 28, 35, 36). Opinions on the effectiveness of this examination are, however, divided (26, 35). Better results of fistula canal assessment and its relation to the anal sphincter (the type of fistula) was obtained in the study of three-dimensional EUS (37). As complementary to transrectal ultrasound, as well as in the case of large narrowing of the anus or with strong symptoms of pain, preventing the introduction of the probe into the rectum, transperineal ultrasound was also carried (TPUS). However, due to the limited range of imaging, the role of TPUS is important mainly in the differentiation of anal fistula with the inflammation of the apocrine glands, which clinically is sometimes very difficult.

In our own study EUS compatibility with the operation in the assessment of the original canal was 73.6%. These results are similar to those obtained by Duminda (71.9%), in a prospective study comparing the results of EUS with intraoperative examination (38).

The results obtained in the MRI are comparable or better than the ones of EUS. Compliance with the Gustafsson et al. material in the assessment of the original canal was 74% (27), in the paper by Hussein et al. 89% (23), and in the studies by West et al. 95% (39). MRI sensitivity in this area was evaluated by Regina 100% (40). In the following publication we are comparing physical examination, EUS and MRI, compliance of EUS and MRI in the evaluation of the original canals amounted to 81 vs. 90% (41).

The effectiveness of EUS in the division of fistulas into simple and complex ones is similar to the study by MRI (sensitivity of 97 vs. 92%) (42). However, MRI is considered a leading method, especially in the diagnosis of complex fistulas, particularly recurrent and emerging in the course of Crohn’s disease (42, 43), including due to the possibility of differentiating fistula canal and branches and postoperative scarring (44, 45).

Results

EUS is a good method for determining the height of anal fistulas. Sensitivity and specificity of the method in the assessment of fistulas are respectively 75 and 91%.

EUS is a good method in the evaluation of the primary canal type, conformity of assessment in this area was 73.9%. Piśmiennictwo

1. Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong WD et al.: Anal fistula surgery: factors associated with recurrence and incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1996; 39: 723-729.

2. Quah HM, Tang CL, Eu KW et al.: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing drainage alone vs. primary sphincter-cutting procedures for anorectal abscess-fistula. Int J Colorectal Dis 2006; 21: 602-609.

3. Iwadare J, Sumikoshi Y, Sahara R: Muscle-filling procedure for transsphincteric fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 1997; 40 (suppl.): 102-103.

4. Wang D, Yamana T, Iwadare J: Long-Term Results and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Patients With Transsphincteric Fistulas After Muscle-Filling Procedure. Poster presentation at the meeting of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois, June 3-8, 2002.

5. Oh C: Management of high recurrent anal fistula. Surgery 1983; 93: 330-332.

6. Ho KS, Ho YH: Controlled, randomized trial of island flap anoplasty for treatment of trans-sphincteric fistula-in-ano: early results. Tech Coloproctol 2005; 9: 166-168.

7. Wedell J, Meier zu Eissen P, Banzhaf G, Kleine L: Sliding flap advancement for the treatment of high level fistulae. Br J Surg 1987; 74: 390.

8. Aguilar PS, Plasencia G, Hardy TG Jr et al.: Mucosal advancement in the treatment of anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum 1985; 28: 496-498.

9. Sonoda T, Hull T, Piedmonte MR et al.: Outcomes of Primary Repair of Anorectal and Rectovaginal Fistulas Using the Endorectal Advancement Flap. Poster presentation at the meeting of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, San Diego, California, June 2-7, 2001.

10. Dupsky PC, Stift A, Friedl J et al.: Endoanal advancement Flaps In Treatment of high anal fistula of Cryptoglandular Origin: Full thickness vs. Mucosal-Rectum Flaps. Diseases Colon and Recum 2008; 51: 852-857.

11. Garcia-Aguilar J, Belmonte C, Wong WD et al.: Cutting seton versus two-stage seton fistulotomy in the surgical management of high anal fistula. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 243-245.

12. Theerapol A, So BYI, Ngoi SS: Routine use of setons for the treatment of anal fistulae. Singapore Med J 2002; 43: 305-307.

13. Williams JG, MacLeod CA, Rothenberger DA: Seton treatment of high anal fistulae. Br J Surg 1991; 78: 1159-1161.

14. Browning G, Parks A: Postanal repair for neuropathic faecal incontinence: correlation of clinical results and anal canal pressures. Br J Surg 1983; 70: 101-104.

15. Jorge JMN, Wexner SD: Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 77-97.

16. Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA: Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1999; 44: 77-80.

17. Perez F, Arroyo A, Serrano P et al.: Fistulotomy with primary sphincter reconstruction in the management of complex fistula-in-ano: prospective study of clinical and manometric results. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 200(6): 897-903.

18. Arroyo A, Pérez-Legaz J, Moya P et al.: Fistulotomy and sphincter reconstruction in the treatment of complex fistula-in-ano: long-term clinical and manometric results. Ann Surg 2012; 255(5): 935-939.

19. Whiteford MH, Kilkenny III J, Hyman N et al.: The standards practice task force, The American Society of Colon ane Rectal Surgeons. Practice parametersfor the treatment of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano (Revised). Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1337-1342.

20. Van Tets WF, Kuijpers HC: Continence disorders after anal fistulotomy. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37(12): 1194-1197.

21. Chung W, Kazemi P, Ko D et al.: Anal fistula plug and fibryn glue versus conventional treatment In repair of complex anal fistulas. Am J Surgery 2009; 197: 604-608.

22. Parks AG, Gozdon PH, Hardcastle JD: A classification of fistula-in-ano. Br J Surg 1976; 63: 1-12.

23. Hussein SM, Stoker J, Schouten WR et al.: Fistula in ano: endoanal sonography versus endoanal MR imaging in classification. Radiology 1996; 200: 475-481.

24. Cataldo PA, Senagore A, Luchtefeld MA: Intrarectal ultrasound in the evaluation of perirectal abscesses. Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 554-558.

25. Lunniss PJ, Barker PG, Sultan AH et al.: Magnetic resonance imaging of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 708-718.

26. Buchanan GN, Bartram CI, Williams AB et al.: Value of hydrogen peroxide enhancement of three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound in fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 141-147.

27. Gustafsson UM, Kahvecioglu B, Astrom G et al.: Endoanal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging for preoperative assessment of anal fistula: a comparative study. Colorectal Dis 2001; 3: 189-197.

28. Navarro-Luna A, Garcia-Domingo MI, Rius-Macias J, Marco-Molina C: Ultrasound study of anal fistulas with hydrogen peroxide enhancement. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 108-114.

29. Choen S, Burnett S, Bartram CI, Nicholls RJ: Comparison between anal endosonography and digital examination in the evaluation of anal fistulae. Br J Surg 1994; 78: 445-447.

30. Cho DY: Endosonographic criteria for an internal opening of fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum 1999; 42: 515-518.

31. Chew SS, Yang JL, Newstead GL, Douglas PR: Anal fistula: Levovist-enhanced endoanal ultrasound: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 377-384.

32. Toyonaga T, Matsushima M, Tanaka Y et al.: Non-sphincter splitting fistulectomy vs. conventional fistulotomy for high trans-sphincteric fistula-in-ano: a prospective functional and manometric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 1097-1102.

33. Deen KI, Williams JG, Hutchinson R et al.: Fistulas in ano: endoanal ultrasonographic assessment assists decision making for surgery. Gut 1994; 35: 391-394.

34. Ratto C, Grillo E, Parello A et al.: Endoanal ultrasound-guided surgery for anal fistula. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 722-728.

35. Ratto C, Gentile E, Merico M et al.: How can the assessment of fistula-in-ano be improved? Dis Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 1375-1382.

36. West RL, Zimmerman DD, Dwarkasing S et al.: Prospective comparison of hydrogen peroxide-enhanced threedimensional endoanal ultrasonography and endoanal magnetic resonance imaging of perianal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 1407-1415.

37. Giordano P, Grondona P, Hetzer H et al.: Three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography is better than conventional anal endosonography in the assessment of fistula in ano. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 607-608.

38. Subasinghe D, Samarasekera DN: Comparison of Preoperative Endoanal Ultrasonography with Intraoperative Findings for Fistula In Ano. World J Surg 2010; 34: 1123-1127.

39. West RL, Zimmerman DDE, Dwarkasing S et al.: Endoanal Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Perianal Fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum 2003: 1407-1415.

40. Beets-Tan RGH, Beets GL, van der Hoop AG et al.: Preoperative MR Imaging of Anal Fistulas: Does It Really Help the Surgeon? Radiology 2000; 218(1): 75-84.

41. Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Bartram CI et al.: Clinical examination, endosonography, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of fistula in ano: comparison with outcome-based reference standard. Radiology 2004; 233(3): 674-681.

42. Sahni VA, Ahamad R, Burling D: Which method is the best for imaging of perianal fistula? Abdom Imaging 2008; 33(1): 26-30.

43. Halligan S, Stoker J: Imaging of fistula in ano. Radiology 2006; 239: 18-33.

44. Morris J, Spencer JA, Ambrose NS: MR imaging classification of perianal fistulas and its implications for patient management. Radiographics 2000; 20: 623-635.

45. Stoker J, Rociu E, Zwamborn AW et al.: Endoluminal MR imaging of the rectum and anus: technique MRI of fistula-in-ano: a comparison of endoanal coil with external phased array coil techniques, applications, and pit-falls. Radiographics 1999; 19(2): 383-398.

otrzymano/received: 2013-05-15 zaakceptowano/accepted: 2013-06-26 Adres/address: *Aneta Obcowska Department of General Surgery, Vascular Surgery Unit, Praski Hospital Al. Solidarności 67, 03-401 Warszawa tel.: +48 (22) 555-10-79 e-mail: aneta_w@poczta.onet.pl Artykuł Przydatność przedoperacyjnego badania endosonograficznego w różnicowaniu przetok odbytu niskich z wysokimi w Czytelni Medycznej Borgis. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chcesz być na bieżąco? Polub nas na Facebooku: strona Wydawnictwa na Facebooku |