|

© Borgis - Postępy Nauk Medycznych 2, s. 147-152

Marcin Błoński, Waldemar Rylski, *Stanisław Pomianowski

Intramedullary Nailing of Femoral Shaft Fractures – Review of Locking Techniques

Leczenie złamań trzonu kości udowej gwoździem śródszpikowym blokowanym – omówienie sposobów ryglowania

Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, the Medical Centre of Postgraduate Education, Professor Adam Gruca Hospital in Otwock

Head of the Department: prof. Stanisław Pomianowski, M.D., Ph.D. Streszczenie

Operacyjne leczenie złamań trzonu kości udowej opiera się na opracowanej przez Kempfa i Grosse'a technice zespolenia gwoździem śródszpikowym ryglowanym. Zespolenia gwoździem śródszpikowym ryglowanym jest stosunkowo mało inwazyjną techniką, zapewniającą stabilne zespolenie umożliwiające wczesne usprawnianie i prawidłowy zrost złamania. Dodatkowo istnieje możliwość rozwiercenia kanału szpikowego. W zależności od wskazań można gwóźdź wprowadzić zarówno od końca dalszego kości udowej, jak i od jej części proksymalnej. W zależności od postaci złamania stosuje się zespolenie statyczne lub dynamiczne. Jedynie w przypadku złamania poprzecznego można zastosować gwoździowanie bez śrub ryglujących. W przypadku złamania poprzecznego w części bliższej trzonu kości udowej, gwóźdź należy ryglować powyżej szczeliny złamania. Analogicznie w przypadku złamania poprzecznego w obrębie części dalszej trzonu kości udowej, ryglowanie wykonuje się poniżej szczeliny złamania. W przypadku wszelkich złamań niestabilnych, ryglowanie należy wykonać powyżej i poniżej poziomu złamania, bez względu na jego lokalizację. W przypadku wykonania zespolenia z ryglowaniem statycznym, należy celem stymulacji powstania prawidłowego zrostu kostnego, wykonać jego wtórną dynamizację. Nie wszyscy operatorzy są jednak przekonani o zasadności wykonywania wtórnej dynamizacji. Słowa kluczowe: złamania trzonu kości udowej, gwoździowanie śródszpikowe, ryglowanie dynamiczne, ryglowanie statyczne

Summary

Surgical treatment of femoral shaft fractures has been based on locked intramedullary nailing since the introduction of its current principles by Kempf and Grosse. Locked intramedullary nailing is a low-invasive technique which allows stable fixation permitting early ambulation and proper fracture union. Intramedullary canal can be additionally reamed depending on the surgeon's decision. If desired, nailing may be performed in both antegrade and retrograde manner. The nail is locked either statically or dynamically using bolts located at its ends according to the fracture type. Only transverse fractures of the middle third of the femur may be treated without locking the nail or with locking only one of its ends. In case of transverse fractures of the proximal part of femoral shaft locking the nail above the fracture is required. Conversely, in case of transverse fractures of the distal part of femoral shaft the nail should be locked below the fracture. All unstable femoral shaft fractures require locking the nail at its both ends regardless of the fracture level. When static locking is done, the nail should be dynamized secondarily after 8-10 weeks in order to enhance proper fracture healing, however this view is not unanimously shared by all surgeons. Key words: femoral shaft fractures, intramedullary nailing, dynamic locking, static locking

Surgical treatment of femoral shaft fractures should permit fast resumption of ambulation and proper fracture union. Locked intramedullary nailing is the mainstay of treatment (1, 2). This technique is a low-invasive, one allowing to shorten the time of hospitalization. Intramedullary nailing permits good fixation of the fracture with proper limb alignment and preservation of periosteal vascularization. Reaming of the intramedullary canal has an additional effect of spongious bone autografting which may stimulate fracture healing (3, 4). Antegrade techniques in which the nail is inserted through the piriformis fossa on the tip of the greater trochanter are less traumatic for the patient and more simple to perform for the surgeon. Obesity, pregnancy, ipsilateral acetabular fractures, ipsilateral lower extremity fractures are among indications for retrograde nailing (5).

Historically one of the most important techniques was the one described by Kuntscher in 1940. It was subsequently upgraded first in 1952 when he adopted elastic reamers and then in 1968 when he started to employ locked nailing. This method was developed in 1972 by Grosse and Kempf working in Strasbourg and has been promoted since then.

Two types of nail locking are currently in use, static and dynamic one. In case of dynamic locking the nail is inserted without bolts or with one or more bolts located in either proximal or distal bone fragment, depending on the fracture type. When this type of locking is used, weight-bearing on the affected limb results in compression of the bone fragments. Rotational movements of the fragments must not occur which explains why this type of locking can be applied only when there is full contact between the fragments. Static locking with bolts on both ends of the nail allows complete stabilization of the fragments (6).

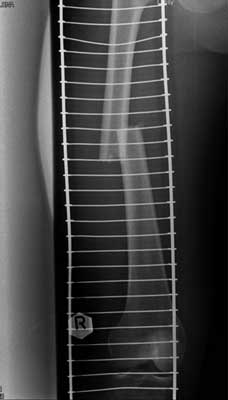

Classic Kuntscher technique is used for treatment of transverse fractures of the middle third of femoral shaft (fig. 1). The nail is inserted without any locking bolts or with the bolts only in the distal fragment when there is a threat of a rotational displacement (7).

Fig. 1. Transverse midshaft femoral fracture.

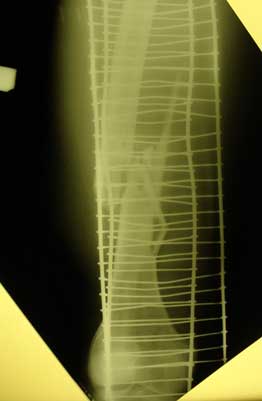

Transverse fractures of the proximal part of femoral shaft (fig. 2) require locking of the nail above the fracture. Conversely, in case of transverse fractures of the distal part of femoral shaft (fig. 3) the nail should be locked below the fracture.

Fig. 2. Transverse proximal femoral shaft fracture.

Fig. 3. Transverse distal femoral shaft fracture.

All unstable femoral shaft fractures require locking the nail at its both ends regardless of the fracture level (fig. 4, 5 and 6).

Fig. 4. Midshaft spiral fracture of the femur.

Fig. 5. Spiral fracture of the proximal femoral shaft.

Fig. 6. Multifragmentary distal femoral shaft fracture.

When static locking is done, the nail should be dynamized secondarily after 8-10 weeks after initial surgery in order to enhance proper fracture healing. Some surgeons decide to perform this procedure only when there is no full contact of bone fragments basing on their experience with patients who had not agreed for nail dynamization and whose fractures had healed with no complications (6). When the nail is dynamized, it is important always to remove the bolts which are more distant to the fracture.

In our centre locked intramedullary nailing has become the standard of treatment of femoral shaft fractures to which other treatment methods are now compared. Below are some of the clinical cases of patients treated in our hospital.

Patient M. L. 22 years old, case no. 1633/2007, motor vehicle injury (fig. 7). The surgery was postponed to the 19th day after the accident due to an upper airways bacterial infection. This femoral shaft fracture was fixed with an intramedullary nail which was locked dynamically (fig. 8 and 9). The radiograph taken 2 years after surgery shows full fracture healing (fig. 10), the next one shows the same patient after the hardware removal (fig. 11).

Fig. 7. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 8 days after injury.

Fig. 8. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 19 days after injury.

Fig. 9. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 19 days after injury.

Fig. 10. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 13 months after injury.

Fig. 11. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 18 months after injury.

Patient R. S., 24 years old, case no. 3166/2006, motor vehicle injury (fig. 12). He was operated on the 11th day after the injury following clinical observation due to concomitant head trauma. The fracture was nailed and static fixation was chosen (fig. 13 and 14). Fig. 15 shows the radiograph taken 3 1/2 months after surgery. The following x-ray pictures show full fracture healing (fig. 16 – taken 2 years after surgery and fig. 17 – taken after implant removal).

Fig. 12. Fragmented fracture of the femoral shaft, day of injury.

Fig. 13. Fragmented fracture of the femoral shaft, 11 days after injury.

Fig. 14. Fragmented fracture of the femoral shaft, 11 days after injury.

Fig. 15. Fragmented fracture of the femoral shaft, 3.5 months after injury.

Fig. 16. Fragmented fracture of the femoral shaft, 25 months after injury.

Fig. 17. Fragmented fracture of the femoral shaft, 25 months after injury.

Patient K. L., 39 years old, case no. 6462/2007, sustained this multifragmentary fracture in a polytraumatic accident (fig. 18, 19) and was hospitalized for 6 weeks in an intensive care unit requiring mechanical ventilation during 2 weeks. The fracture was nailed on the 5th day after the accident and the nail locked statically (fig. 20). Three other radiographs show the fracture site 1.5 months, 13 months and 2.5 years later respectively; the last one was taken after the implant had been removed (fig. 21, 22 and 23).

Fig. 18. Multifragmentary fracture of the femoral shaft, day of injury.

Fig. 19. Multifragmentary fracture of the femoral shaft, 5 days after injury.

Fig. 20. Multifragmentary fracture of the femoral shaft, 5 days after injury.

Fig. 21. Multifragmentary fracture of the femoral shaft, 1.5 months after injury.

Fig. 22. Multifragmentary fracture of the femoral shaft, 13 months after injury.

Fig. 23. Multifragmentary fracture of the femoral shaft, 30 months after injury.

Patient W. L., 17 years old, case no. 749/2007, treated outside our hospital with plate fixation (fig. 24). After 3 months after his initial surgery he was re-operated in our centre due to loss of fixation. The plate was removed and the fracture was fixed with an intramedullary nail with static locking (fig. 25 and 26). The nail was subsequently dynamized because of delayed union (fig. 27). 17 months after surgery the fracture healed (fig. 28) and the implant was removed (fig. 29).

Fig. 24. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 1.5 months after injury.

Fig. 25. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 4 months after injury.

Fig. 26. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 4 months after injury.

Fig. 27. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 8 months after injury.

Fig. 28. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 17 months after injury.

Fig. 29. Transverse femoral shaft fracture, 18 months after injury.

Locked intramedullary nailing is an effective method of treatment which allows stable fixation and early ambulation. It has gained worldwide approval since its invention and is now widely used. The cases discussed above are typical examples of managing femoral shaft fractures using this technique. We believe that this procedure together with correct post-operative treatment and physiotherapy allow the patient to regain his previous level of activity in reasonable time. Final result is however dependent on many other factors, including social and psychological ones. We believe that this method serves as an excellent example of how modern treatment methods used in orthopaedic surgery permit patients to recover their health while in the past the same injuries were often associated with permanent disability and even premature death. Piśmiennictwo

1. Winquist RA, Hansen ST Jr, Clawson DK: Closed intramedullary nailing of femoral fracture: a report of five hundred and twenty six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984; 66: 529-539.

2. Brumback RJ, Ellison PS Jr, Poka A et al.: Intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures, I: Decision making errors with interlocking fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 1441-1452.

3. Shepherd LE, Shean CJ, Gelalis ID et al.: Prospective randomized study of reamed versus unreamed femoral intramedullary nailing: an assessment of procedures. J Orthop Trauma 2001; 15: 28-33.

4. Tornetta P 3rd, Tiburzi D: Reamed versus nonreamed antegrade femoral nailing. J Orthop Trauma 2000; 14: 15-19.

5. Ostrum RF, DiCicco I, Lakatos R et al.: Retrograde intramedullary nailing of femoral diaphyseal fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1998; 12: 464-468.

6. Kempf I: Gwoździowanie śródszpikowe ryglowane w leczeniu złamań kości długich. From materials of „IV Śląskie Sympozjum Traumatologiczne”, Katowice 1997.

7. Semenowicz J: Operacyjna technika śródszpikowego zespalania złamań trzonu kości udowej gwoździem Grosse i Kempfa. From materials of „IV Śląskie Sympozjum Traumatologiczne”, Katowice 1997.

otrzymano/received: 2009-12-08 zaakceptowano/accepted: 2010-01-06 Adres/address: *Stanisław Pomianowski Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology Medical Centre of Postgraduate Education Professor Adam Gruca Hospital in Otwock 13 Konarskiego Str., 05-400 Otwock tel.: +48 (22) 788-56-75 e-mail: spom@spskgruca.pl Artykuł Intramedullary Nailing of Femoral Shaft Fractures – Review of Locking Techniques w Czytelni Medycznej Borgis. |

Chcesz być na bieżąco? Polub nas na Facebooku: strona Wydawnictwa na Facebooku |